The woman known as Matilda may seem unremarkable; however, she was anything but! As a housebound slave, she taught herself how to read, and she would inspire countless more runaway slaves to take legal action.

By Sean E. Andres, updated 27 Sep. 2023

Matilda’s birth around 1816 was one that was common of enslavers who raped enslaved women. She was born in southern Missouri to an enslaved “mulatto” mother and her owner Larkin Lawrence. Since Matilda could pass as white, Larkin raised her as his servant and dependent, belonging to no community but to him. The whole area knew her story, so white society barred her and her father did not permit her to interact with blacks. Matilda was in a prison of isolation. She used her forced shut-in status to learn to read, using the books in Larkin’s library. When Matilda was 16, her mother died, leaving Matilda to take up her work as housekeeper on top of her work as Larkin’s personal assistant.

In the winter of 1836, Larkin took Matilda with him as his daughter to the east coast. Now exposed to the outside world and opportunities of the North, she eagerly learned more, especially of freedom and her own condition of slavery. Larkin declined her continued requests for freedom. She even said she promised to return with him to work for him, as long as she was free.

Concerned about Matilda’s newfound wishes, Larkin set sail for Missouri, docking at Cincinnati’s wharf in May 1836 and spending the night at a hotel near there, intending to resume passage on a steamboat the next day. There, Matilda left in the middle of the night and sought refuge in Church Alley with a local black barber. An angry Larkin left a few days later.

In October 1836, the abolitionist Birneys hired her as a chambermaid and nurse. The Birneys adored her, though she didn’t talk about her past. She had twisted her story to be a white woman born into poverty in Missouri with a dead mother. She was developing a new home, a place where she was loved. But not loved enough to have revealed her secret heritage, even to the known abolitionist family, in this time of immense turmoil and fear.

The mobs increased in violence as Birney’s voice grew stronger and more persuasive, taking to violence against Blacks in Church Alley and attempted violence against Pugh, Birney, and Chase. This was a dangerous city for Matilda to be in, if anyone ever found out that she was not 100% white. With Cincinnati being a border city, it was a battleground for abolition, and abolitionists could not declare themselves so, lest they be attacked. Rather, they labeled themselves as proponents of free speech, and most were in the Semi-Colon Club (the Mitchels, Stowes, Footes, Beechers, Carys, etc.). Birney was first to shake the city up as an outspoken self-labeled abolitionist and former slave owner, and Matilda was about to help… but not on purpose.

In early March 1837, John W. Riley approached her in the streets and charged her with being a runaway slave, according to a 1793 law. According to Riley, Larkin Lawrence hired him as a bounty hunter to track down Matilda for fleeing. However, Riley was a bounty hunter after one thing: money. Birney plotted to have Matilda stay with a friend in western New York until this passed over, but the house was under constant surveillance by Riley and his hired crew. Matilda was arrested on 10 March 1837.

While detained, James Birney hired his friend Salmon P. Chase as Matilda’s defense attorney. Usually, runaway slaves were sent to appear before a magistrate without a jury and sent back with the claimed owner. Chase and Birney would try to change that. The two men had been friends since 1835, and he taught Chase anti-slavery rationale as they spent many late nights conversing in Birney’s library. Chase appeared before Judge Este, who had already made up his mind before Chase spoke.

On 11 March 1837, at 9:30 a.m., Chase made a widely-read, logos-based defense of Matilda’s right to freedom that would rock the nation to its core in Matilda Lawrence v. Ohio. He asked not for sympathy but for careful ears in this case under national spotlight. The results of this case could forever influence U.S. democracy, law, and society. He insisted that this fame and any emotions toward Matilda—racist or sympathetic—do not intervene in sound judgment.

Matilda had committed no crime, “unless color be a sufficient cause of detention: and if so—if color be sufficient cause of imprisonment, let us know the exact shade. The time has not yet arrived in Ohio, when color implies either crime nor bondage. And far distant be the day! For that day will not come, till the solid foundations of our state institutions shall be upheaved and scattered by the volcanic energies of revolution.”

He went on: “The state courts were created for the very purpose of protecting personal liberty, and all the provisions of the habeas corpus act were intended as its muniments and safeguards.” Personal liberty is something everyone should care about and relate to, he argued. If your liberties were encroached upon, would you fight for them?, he asked. So why not allow others the same right? He used the example that if any white person has been taken to court without a jury concerning work, paid or unpaid, or stolen property, the would be anarchy. This was quite genius to enlist the white working class empathy. They worry more about their personal liberties being taken from them than any upper class white folks would. “There is no security for the poor, the ignorant and the unfriended,” speaking directly of Matilda. No one’s freedom is safe. Chase borders on the edge of slippery slope tactics, but relies heavily on constitutional reason. Matilda, as a mulatto passing off as white in Cincinnati, became more than a symbol of slavery; she became a symbol for workers, regardless of skin color. Or at least she should have.

Chase also argued that many runaways were not given a right to a fair trial by jury, rendering the act unconstitutional, repugnant to the ordinance of 1787. Federal law superseded state law and purports to ensure “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The writers of the constitution would have set specific provisions regarding slavery and race, and offices would have been accordingly appointed. There were no such things established. Additionally, her imprisonment is illegal, according to the 4th and 5th Amendments. The four Ohio laws concerning enslaved people’s rights do not give reason for Matilda’s arrest either. Chase requests that Matilda be freed from prison because it is her constitutional right—but moreso her natural and divine right as a human.

After Chase’s eloquent argument, Judge Este ruled that Matilda be returned to slavery. The terrified, screaming Matilda was sent back to an independent prison in Covington, Kentucky. Here, she could not be saved. She was now outside of Ohio law and the threat of being taken to a higher court. That night of 11 March 1836, she was secretly placed on a steamboat bound for New Orleans. There, she was sold into slavery once more and was lost in record. The high price on her head gave Riley and his Democratic lawyers a hefty reward.

Birney was now brought before the court, indicted for harboring a fugitive slave. He lost, but Chase took his case to the upper courts. The Ohio State Supreme Court trial lasted for over three hours with William Birney being used as a witness against his own father. Birney won, and the lower court sentence was reversed. Through Pugh’s new office at Main and 5th, Birney published and distributed Chase’s defense to those within the realm of law.

Sadly, the two white men who fought for Matilda went on to have bigger careers while Matilda suffered in slavery, probably never allowed to read again. From Matilda’s case was born Constitutional law, and it made Chase known as the “Abolitionist Lawyer” or “Attorney for Runaway Slaves,” an adviser for cases all over the North and Northwest and labels we wore with pride.

Matilda, in all her efforts for freedom and with that small taste of it, spurred a revolution. Runaways all over the North began to apply for writ of habeas corpus to fight for fair trials. Free states, moved by Matilda and reasoned by Chase’s defense, began to pass personal-liberty laws, “designed to secure the right of trial by jury to every person claimed as a slave, and to punish as kidnappers all persons aiding or abetting in delivering as a slave any person not proved to have escaped from a slave into a free State.” Many of these cases did not end well, especially in Cincinnati, where those in judiciary roles were yet swayed by the power of slavery, tradition, proximity to the South, and by pressure of white anger. But Matilda changed how many people viewed the legal system and gave hope to thousands of southern refugees.

Want to take a Matilda pilgrimage in Cincinnati?

I’m sorry there’s really nothing to see regarding Matilda’s journey. We don’t have a diary or letters from her, so it’s hard to make more of a Matilda trip, and none of the buildings stand anymore. But you can make the most out of it as you track her journey to attempted freedom.

-

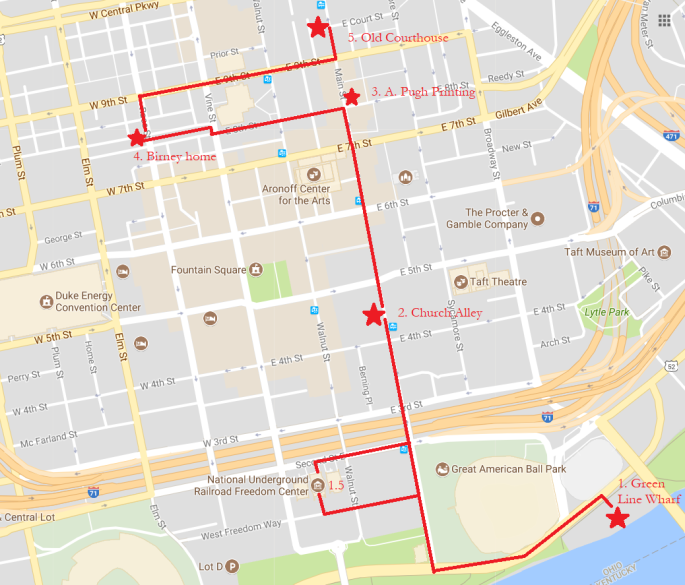

Walk along the river: Go to the old Green Line Wharf, about where the docks are in front of U.S. Bank Arena, between Taylor Southgate Bridge and Broadway, along the Ohio. This would be a great opportunity to fit in a trip to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center on the banks, where Little Africa used to stand.

-

Take me to church: From the Banks, head on up to what was known as Church Alley, between 4th and 5th and Walnut and Main, behind the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland building, where Matilda sought refuge and where the mobs attacked.

-

Feeling philanthropic? On the way to the next destination, you can see where Achilles Pugh’s office was—where Birney’s Philanthropist was printed and where Matilda may have sent messages from the family.

-

Home is where the car is: If you get hungry on the way to see where Matilda worked for the Birneys, you can stop at Fins Feathers & BBQ or Cafe de Paris on Garfield Place, or any other place you see along the way. Take a walk through Piatt Park, Cincinnati’s oldest park. At the corner of 8th and Race, you’ll be standing in front of where the Birney house (Franklin Hotel) was. You can still see the alley between the two building sets between the parking lot and Ron Hamilton Photo. The buildings would have stretched into what is now Piatt Park, as 8th Street was only E Garfield Pl at the time. The Birney house would have been likely on what is now W Garfield/8th.

-

Porkopolis: On Main at the end of Court, you’ll see the current Hamilton County Courthouse. Where the east side of the building is, you’ll find the site of the courthouse Matilda’s case was held in. It was a small two-story building that caught fire from the pork plant next to it.

- Explore the world: Tag us in your adventures to honor Matilda on instagram, twitter, or facebook with hashtags #queensofqueencity and #MatildaLawrence. Tag us in any other women-centric adventures, too!

Photo Gallery

Notes

The Democrats were traditionalist, slave-holding sympathizers, and Republicans tried to be progressive liberals. The Liberty party was born out of abolition because Republicans weren’t progressive enough.

I’m trying to find out what happened to Matilda—to whom she was sold and if she had children. If you know or know of ways, please contact us.

Concerning photos: All photos are taken/owned by Queens of Queen City or given permission for use here only and are indicated when originating elsewhere. Please do not reproduce without our consent or the originators’ consent, respectively.