Though she wasn’t in Cincinnati long, Edith Fossett managed to make quite an impression through her legacy of bringing the White House kitchen’s French cuisine to Cincinnati’s high society.

By Sean E. Andres, updated 27 Sep. 2023

Edith “Edy” Hern was born one of twelve children to David and Isabel Hern in 1787, all enslaved by Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. By her early teens, Edy co-headed the kitchen with her cousin Peter Hemings, who inherited the kitchen duties from his older brother James, who learned French cooking in France when Jefferson stayed there. The French food revolution was vastly different from the majority of the mushy, bland white American cuisine – texture and flavor were enhanced, and there were more vegetables and more variety of them.

When Francophile Jefferson was elected president, he brought on French chef Honoré Julien to be head chef at the White House. When Julien could not make muffins like Peter Hemings back in Monticello, he forced Edy to come to the White House in 1802 to understudy Julien, leaving her new husband Joe Fossett (Sally Hemings’s nephew by Mary Hemings-Fossett) behind. Jefferson’s guests noted that “never before had such dinners been given in the President’s House.” Benjamin Latrobe wrote that the meals were “cooked rather in the French style” and the dessert was “extremely elegant.” As chef, received a monthly two-dollar gratuity, but not a wage.

Some examples of her cooking are in one of Jefferson’s final dinner parties. The first course: partridge with sausage and cabbage, ham, beef bouilli, bear meat, cresoniѐre, potatoes, rice, spinach, beans, lamb’s-lettuce salad, and pickles. The desert: custard with cream, apples in a thin toast. After dinner, wine was served with charcuterie boards of olives, apples, oranges, nuts, and more. Other desserts guests frequently praised were ice cream enclosed in pastries. While here, Edy made friends in the free Black community, which later Jefferson accused of harboring her brother Thurston when he ran away from enslavement because of their connection to Edy.

In 1806, Jefferson was surprised to find that Joe, whom Jefferson considered privileged, ran away. But Joe ran away to see Edy, for which he was jailed upon leaving the White House. That same year, her sister-in-law Frances “Fanny” Gillette Hern joined her in the kitchen.

When she returned to Monticello in 1809, she became head chef, teaching her sons William and Peter. Julien helped set up the kitchen, staying for a few weeks. With her family, she likely lived in the cook’s room, a 10’x14’ room with a brick floor in the south dependencies of the main house. Her cooking was “half Virginian, half French style, in good taste and abundance,” as Daniel Webster noted. George Ticknor said, “The dinner was always choice, and served in the French style.” To b clear, this was not fusion; the food styles were kept separate. While she fed the Jefferson and guests her French and Virginian cuisines, she lived on a paltry peck of cornmeal and pound of pork per week. However, she probably supplemented her diet, along with her family’s, with scraps. Each family also supplemented their diet with wild game and their own gardens and poultry, which also got them money when they sold their produce to Monticello.

After his death in 1826, Jefferson freed Joe by his will. It was 4 July 1827. Edy and eight of her ten children were sold to at least four different enslavers. Jesse Scott, a freed man of color who married Joe’s sister Sally, purchased Edy and her two youngest children William and Daniel for $505 to help keep the family together. Joseph bought Edy, five of their children, and four of their grandchildren and freed them in September of 1837. Edy’s in-laws and some of her children had already settled in Ohio at Chillicothe, but Cincinnati held more promise, so the family settled there by 1843. There, Edy helped her sons establish a successful catering business, which through hard work, became the most sought-after catering business in the city, which lasted well into the 1900s.

Edy died on 10 September 1854 at 65. Soon her husband Joe followed on 19 September 1858 at the age of 77. They are buried together at Union Baptist Cemetery with Peter and Sarah Mayrant Walker Fossett sharing a headstone and Jesse Fossett next to them. Unfortunately, their graves are in major neglect and disrepair but have gotten funding for preservation.

Take the Edy Tour

- Oolala: Since we’ll be at the Banks, have lunch at the Yard House. However, if you want to be French about it to sample Edy’s cuisine, Restaurant L down the road is fancy and expensive. If you want French cuisine elsewhere, start at French Crust Café and Bistro across from Findlay Market.

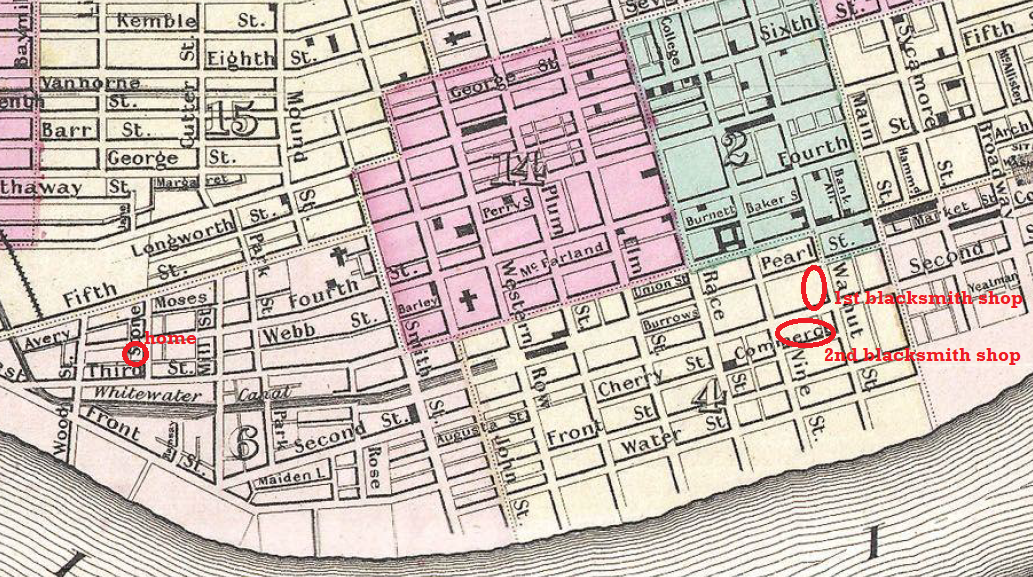

- For Freedom: Tread on the site where Edy’s husband Joe would have worked as a blacksmith. The first location was razed, but the east wing of the National Underground Railroad Museum was built atop it. The second blacksmith shop was across from it on what’s now Freedom Way, where the Yard House or the grassy park west of it lies. While you’re there, take a trip to honor Edy and Matilda at the museum.

- A Stone’s throw away: Then head to the west side on your way to the next stop and drive past where the home at Stone Street (now known as Stone Chapel Ln) was located. Linn Street goes right over where it stood.

- Visiting the stone: Finally, go to Union Baptist Cemetery in Price Hill. The Fossett graves are located to the right before the historic church in the middle of the cemetery. Donate to the cemetery at GoFundMe.

- Want seconds? If you’re so inspired, take a weekend vacation to Monticello in Charlottesville, where Edy grew up and learned how to cook as a slave. They do a great job of telling the slave stories now. There used to be a French restaurant there named after Edy with her portrait, but it looks to be closed now.

Sources

- Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens by Wendell P. Dabney

- City of Cincinnati Map, 1885, by Colton

- Getting Word by Monticello

- Kitchen Sisters

- Newspapers.com

- Colored Conventions Project

- U.S. Census Records

- Williams Directory

- Lucia Stanton’s “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

All photos were taken by Andres.

Hi nice reading youur post

LikeLike